Understanding increased seal bycatch

Project manager Dr Javed Riaz fitting a satellite tracking device to a South American fur seal in the Falkland Islands. Credit - SAERI.

The right type of bap: Understanding seal bycatch to inform a Bycatch Action Plan (BAP)

The Falkland Islands are a small island nation, nestled far away in the remote South Atlantic. Despite its geographical isolation, its commercial fishery plays an important role in sustaining global seafood markets. If you’re enjoying a delicious platter of calamari in southern Europe, there’s a good chance it comes from the cold sub-Antarctic waters of the Falkland Islands. In fact, the Falkland Islands marine environment is actually considered one of the most productive marine ecosystems in the world. It forms the basis of a thriving commercial fishery, which is the lifeblood of the Falkland Islands economy (~ 60% annual GDP). These productive waters also support significant populations of seals, penguins, and flying seabirds, including a whopping 50% of the global population of South American fur seals! Blessed with such rich ecosystem value, it’s no surprise long-term sustainability of the fishery and responsible marine management is a central objective of the Falkland Islands Government.

"There is an urgent need to understand why there has been an increase in seal-fishery interactions, and how this ongoing problem might evolve in future."

In recent years, there has been a sudden and unprecedented increase in seal-fishery interactions within the Falkland Islands Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The number of fur seals being accidentally caught in fishing nets has increased by approximately 900%. To put that statistic into perspective, only 13 incidental mortalities had previously been reported over an 18-year period between 1998 – 2016, however in a single season in 2017 there were 140 seal mortalities recorded. Fortunately, industry and government have worked hard to reduce mortality to very low levels with the introduction of Seal Exclusion Devices – basically an escape hatch allowing seals to exit nets when caught. However, seal-fishery interactions remain at unprecedented levels today and the reasons driving this sudden surge remains a mystery. This is of concern because continued interactions between commercial fisheries and fur seals in the Falkland Islands may impact the conservation status of this iconic species. Recognising the need for long-term sustainability of the Falkland Islands economy and for holistic marine management, there is an urgent need to understand why there has been an increase in seal-fishery interactions, and how this ongoing problem might evolve in future.

Our Darwin Plus project aims to shed light on this important issue. Working in close collaboration and partnership with the Falkland Islands Government Fisheries Department and the Falkland Islands Fishing Companies Association, our research aims to advance understanding of seal-fishery interactions in the Falkland Islands. This will enable future mitigation measures and action plans to be developed to support long-term marine management objectives.

To understand the nature and extent of seal-fishery interactions in the Falkland Islands, a fundamental question we must assess, is whether seals and commercial fisheries are competing for resources. However, this is not a straightforward question. For starters, remarkably little is actually known about the foraging and movement ecology of South American fur seals. We don’t yet have a good understanding of where seals are foraging while they’re at sea and what prey items they rely on. If we know more about these components of fur seal foraging behaviour and habitat use, we can begin to piece together an understanding of how, why, and the extent to which they are interacting with the Falkland Islands fishery.

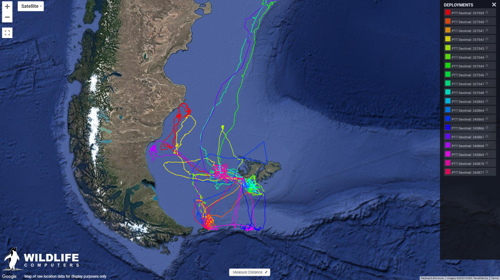

Our project will gather this critical information using state-of-the-art seal tracking devices. This requires us to work hands-on with the seals, attaching small tracking devices on their backs. Similar to the GPS technologies we all have on our phones, these seal tracking devices transmit via satellite and provide us with valuable information about where seals are going and how they’re behaving while they’re out at sea. Importantly, these data can also help us understand whether seals and commercial fisheries overlap in time and space, and in which areas they’re most likely to be interacting.

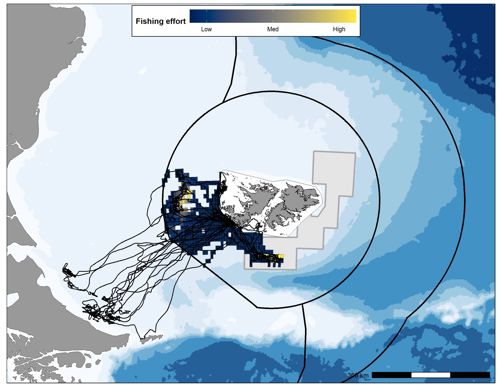

From our research, we’ve learnt that fur seals in the Falkland Islands are impressive ocean explorers. They roam far and wide across the Patagonian Shelf, venturing into multiple fishing jurisdictions, travelling thousands of kilometres, and even diving down to depths of over 300m in search of food! But what’s really interesting is that our tracking work has revealed just how important the Falkland Islands EEZ is to this fur seal population. Not only are seals spending the majority of their time at sea within the Falkland Islands EEZ (around 65%), but they also seem to be concentrating their foraging activity in the same key habitats targeted by the commercial trawl fishery. Our research has demonstrated a distinct overlap between seal foraging activity and squid and finfish commercial fishing efforts. This suggests seals and commercial fisheries are visiting the same habitats and are likely competing over the same squid and finfish stocks.

While this research represents an important first step in building our understanding of seal-fishery interactions in the Falkland Islands, more work is required to explain why there has been a sudden increase in interactions since 2017. It might be that seals and fisheries have always targeted the same habitats around the Falkland Islands, and that there is something else at play driving increased interactions. One thing is for sure, though – the sudden increase in seal-fishery interactions has coincided with significant changes in the Falkland Islands marine ecosystem. In recent years, there have been dramatic shifts in the composition and abundance of squid and finfish resources around the Falkland Islands EEZ. On the one hand, squid are being harvested in record-high quantities; but on the other hand, historically dominant southern blue whiting and rock cod stocks have almost entirely collapsed as a result of sustained overfishing in the region. Furthermore, we also know fur seal population dynamics have been changing over the past few decades, dramatically increasing in both population size and the number of breeding colonies. Clearly, disentangling the complex interactions between seals, fisheries, and the regional marine environment is no easy task.

Through our DPLUS168 project, we will continue to develop an understanding of the factors contributing to increased seal-fishery interactions within the Falkland Islands EEZ. In future work, we will conduct a comprehensive investigation of fur seal diet to better understand the relative importance of commercially caught species, and whether there have been any changes in diet over time. We also plan to develop mathematical models which use a broad range of fisheries and environmental data to tell us which factors are most likely to influence seal-fishery interactions in the Falklands EEZ. Ultimately, our research is vital in supporting conservation efforts for this globally significant fur seal population and contributing to long-term sustainability and marine management objectives of the Falkland Islands fishery.

Written by Dr Javed Riaz. For more information on this Darwin Plus Main project DPLUS168, led by the South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute (SAERI), please click here.

Back

Back