Successful stories of seabird conservation

Field team taking spectral profiles of vegetation in a burrowing petrel colony. Credit - Connor Bamford and Nathan Fenney.

A bright green clue: Fertilised vegetation and satellite mapping of burrowing petrel colonies

South Georgia, a remote and spectacular UK Overseas Territory in the South Atlantic, is home to an array of seabirds, including burrowing petrels, albatrosses, penguins, and shags.

Rats and mice, introduced in the late 18th century by sealers and whalers, rapidly multiplied and preyed on the eggs and chicks of burrow- and ground-nesting birds. While some burrowing species, like the White-chinned petrel, persisted in rat-infested areas, their numbers were severely reduced. The smaller burrowing petrel species, however, were unable to breed in the presence of rodents. These invasive rodents also disrupted the island’s invertebrate and plant communities, destabilising the fragile ecosystem. Reindeer, introduced between 1909 and 1925 by Norwegian whalers, exacerbated the problem by overgrazing, which exposed burrow entrances and made them prone to collapse.

To restore the wildlife on the main island, an eradication project was carried out by South Georgia Heritage Trust between 2011 and 2015, targeting rodents using poison bait. The island’s natural division by glaciers made this effort feasible, and in 2018, South Georgia was declared rodent-free. A separate eradication campaign led by the Government of South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands led to the removal of reindeer by 2015; vegetation began to recover, improving habitats and supporting the return of burrowing petrels.

White-chinned petrels breed along the steep coastline of the main island but generally at lower densities than on the outlying islands. Their loud rattling calls at the colony can be heard in the evening and at night from nearby ships at anchor or research stations. However, monitoring these seabirds remains challenging due to their underground nests, as burrows in dense tussac are difficult to count over large areas. It is also unclear which areas have always been occupied, where numbers may be increasing as a result of the rodent and reindeer eradications, and whether petrels have expanded into new locations.

To address these challenges, a new project is utilising cutting-edge satellite and spectral imaging technology to map seabird habitats and provide deeper insights into the distribution and recovery of burrowing petrels.

Fertilised vegetation as a clue for satellite mapping

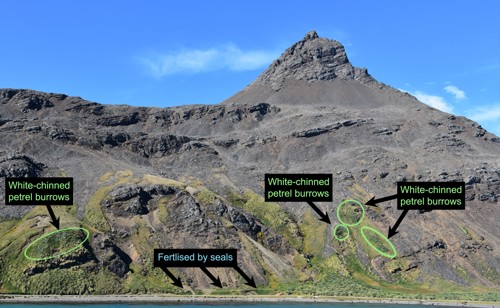

It is well known that tussac around dense colonies of burrowing petrels appears brighter green than the surroundings due to the fertilising effect of the guano. This sparked the idea for this project: could the presence of fertilised vegetation patches be used to map the recovery of White-chinned petrels and other burrowing petrels across South Georgia using satellite imagery?

There are two key challenges. First, these green patches are often quite small, just a few meters or so in diameter, making them difficult to identify in satellite images. Second, we not only need to distinguish between fertilised and unfertilised vegetation, but also account for the effects of other species, such as fur seals, which also enrich grassy vegetation when they haul out in large numbers. To help with this, factors such as distance from the shoreline, aspect, and the slope of the terrain will be used to differentiate between petrel nesting areas and seal haul-out sites.

Ground data collection at King Edward Point

In November 2024, a British Antarctic Survey field team set out for King Edward Point in South Georgia to collect crucial data from areas where burrowing petrels had recently been surveyed on the ground. Their goal was to use a hand-held spectrometer to gather spectral profiles from the different types of vegetation and seabird habitats.

A hand-held spectrometer works by emitting light onto a surface and measuring the amount of light that is reflected back. The instrument analyses this reflected light across different wavelengths, providing a spectral signature that reveals the unique characteristics of the material being studied—whether it is plant leaves, soil, or other features of the environment. By comparing these spectral signatures, researchers can differentiate the types of vegetation and whether they have been fertilised.

Arriving just after the snow had begun to melt, the team faced a tough start. They had to wait for the thaw, and once the weather cleared, they battled strong winds to complete their scans. Despite these obstacles, the team successfully completed 18 scans and has since rotated in new members to continue the work through mid-January.

The team systematically scanned areas of tussac grass occupied by burrowing petrels, seals, or unused by birds or mammals. Each spectral scan covered a 30 x 30 cm area, collecting data from both the centre and edges of each patch. This information is vital for fine-tuning satellite data currently being collected across the entire South Georgia coastline. The calibrated imagery will be used in habitat models to predict the presence of potential burrowing petrel colonies across the entire island group. These will be compared with known colony locations near the British Antarctic Survey research stations at King Edward Point and Bird Island, and with new ground surveys elsewhere to assess the accuracy of the habitat models.

Satellite imagery of South Georgia was captured until the end of January by Maxar Technology, with additional imaging through March 2025 to ensure clear, cloud-free shots. Although the main focus of our project is to use these very high-resolution (30 cm) multispectral images to map burrowing petrel colonies, we will also evaluate their potential for mapping the extent of colonies of other seabirds, including albatrosses, shags and penguins.

Written by Marie Attard, Richard Phillips, Ellen Bowler, and Peter Fretwell. For more information on this Darwin Plus Main project DPLUS187, led by British Antarctic Survey (BAS), please click here.

Back

Back