Ocean literacy and biodiversity stewardship

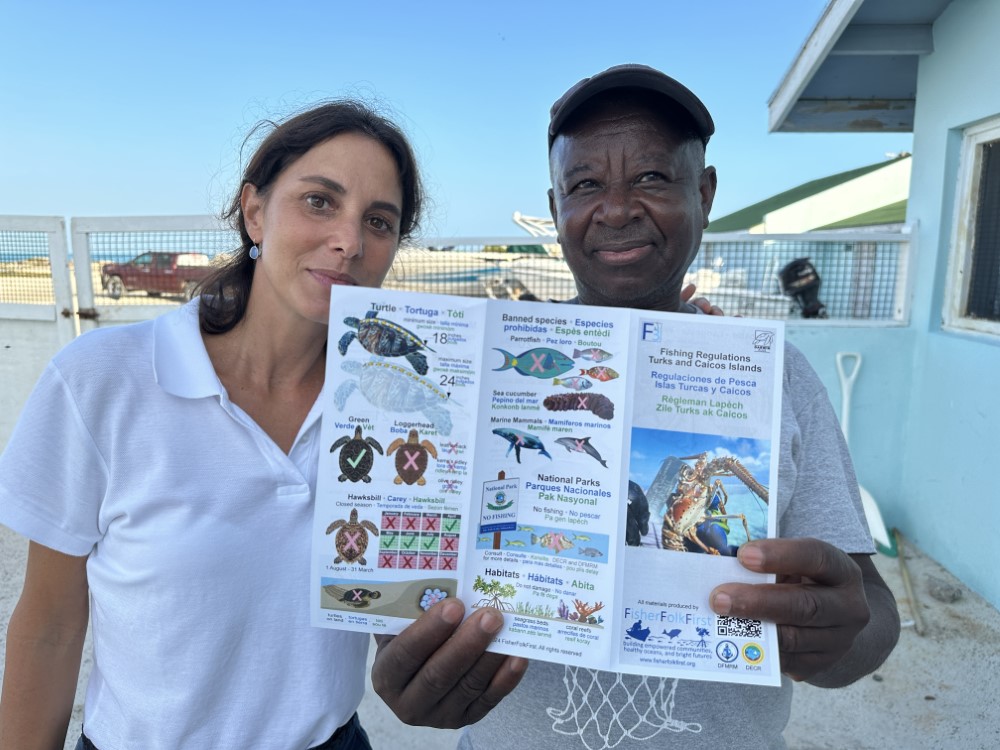

Daniel Dummond, employee of Provo Seafood processing plant, displays the regulations brochure with Marta Calosso, FisherFolkFirst. Five Cays, Providenciales. Credit - John Claydon.

Working with fishing communities to develop ocean literacy and biodiversity stewardship in the Turks and Caicos Islands

Fisheries were once the bedrock of the economy in the Turks and Caicos Islands (TCI), a UK Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. Free-diving fishers working from small vessels caught spiny lobster, queen conch, and various fishes which were then processed and exported. While the country’s fisheries persist, the TCI have now developed into a luxury tourist destination and centre for offshore finance. Although the fleet and fishing methods have remained largely unchanged for over 50 years, fishing regulations in the TCI have evolved constantly over this period.

Currently, the legislation includes a combination of size limits, closed seasons, quotas, bans, gear restrictions, and licencing requirements that address over 20 different species, many of which are of conservation concern, and includes almost 30 separate areas closed to fishing. These laws are designed to support sustainable livelihoods but, despite their increasing complexity, there has never been an easily accessible summary document, and little or no information has been provided to explain the ecological reasons behind the rules. These issues are exacerbated for the large component of non-English speaking fisherfolk from Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and for those who struggle with literacy. As a consequence, fisherfolk do not fully understand the regulations; they are less inclined to support restrictions to their fishing; compliance is compromised; and small-scale fishers have become further marginalised from decision-making processes.

Dominican seafood cleaners Marisol Rosario and Ingrid Camilo linking to the regulations website through the QR code on the poster held by John Claydon, FisherFolkFirst, at Caicos Seafood processing plant, South Caicos. Credit - Marta Calosso.

FisherFolkFirst, a nonprofit organisation registered in the TCI, sought to address this problem through its recent Darwin Plus Local project, ‘Developing biodiversity stewardship among TCI fishers through outreach and education.’ Empowering small-scale fishing communities is fundamental to the work of FisherFolkFirst, and thus this project employed a co-design approach that engaged fishers, fish workers, seafood processors, and fisheries enforcement officers in almost all steps of the process, from planning to implementation. In fact, the original idea for the project arose from a conversation with a former commercial fisher who currently works for the TCI Department of Fisheries and Marine Resources Management (DFMRM). He stressed the importance of explaining the ecological reasons behind the fishing regulations, ‘not just telling fishers what they are not allowed to do.’

FisherFolkFirst started working with the fishing community and DFMRM to identify the most appropriate way to convey information about the regulations in multiple languages (English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole), and to cover a wide range of educational backgrounds and levels of literacy. Together, it was decided to develop a combination of print, online, and video educational materials tailor-made for fisherfolk. The materials include:

- Hundreds of 3-fold brochures distributed throughout the islands to a wide range of stakeholders.

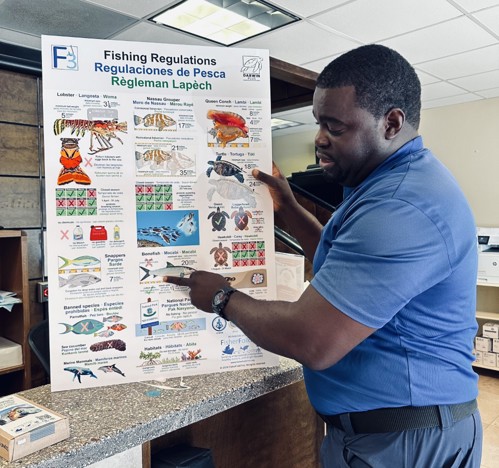

- Portable pull-up banners on display at every DFMRM office and available to transport to consultation meetings, school visits, and other outreach activities.

- Weatherproof posters placed at strategic landing sites on the main fishing islands of South Caicos, Providenciales, and Grand Turk.

All materials have a QR code linking to a cell phone-friendly website that summarises TCI fishing regulations.

An important goal of the project was to ensure that the reference materials were as accessible as possible to all demographics of fishers and fish workers, and so multiple drafts were field-tested, and successive feedback was incorporated into the final designs. For example, to illustrate size limits and closed seasons, more simple and more intuitive life-like images were preferred over tables summarising regulations which are more typically used in other countries.

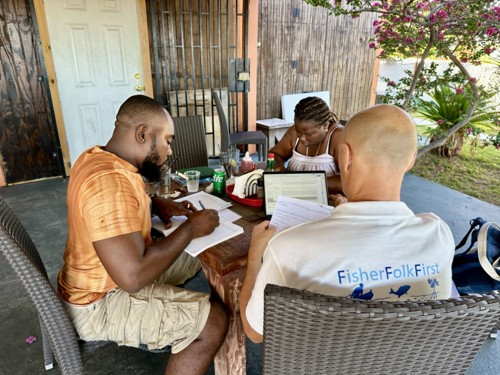

In addition to employing professional translators, fishers and fish workers from Haiti and the Dominican Republic provided invaluable assistance with translation. Verifying the common names of some fish and other species would have been impossible without their help. For example, although the official translation of ‘parrotfish’ in Creole is ‘pwason jako’, Haitians in the TCI typically use the word ‘boutou’. Further engagement with the fishing community included chartering local fishing vessels to film commercial fishers catching lobsters, conch, fish, and turtles, measuring their catch, and explaining size limits. FisherFolkFirst also employed three different women with ties to the fishing community to narrate the videos in English, Spanish, and Creole (see videos below).

Each step of the project was an opportunity to embrace the concept of co-design by engaging with the fishing community so that the finalised materials reflected their input, knowledge, and expertise. In addition to providing useful, practical resources, other key aims of the project were to develop ocean literacy, foster biodiversity stewardship, and empower fisherfolk of all genders and nationalities. Therefore, each step of the project was also an opportunity for outreach and education through talking about the regulations, the important aspects of ecology, and the overall benefits for fisherfolk, fisheries, and biodiversity. This included both the initial stage of ideation and planning, and the final stage of distributing the materials throughout the islands and showing the community how their input improved the final products.

The co-design approach employed during the project brought many value-added benefits: it improved the project’s outcomes by tapping into local knowledge and expertise; it empowered the fishing community by recognising the value of their perspectives and concerns; it built collaborations and partnerships, paving the way for future successes; it bridged the gap between fisherfolk and government; and, finally, it enhanced the project’s enduring legacy and impact. Overall, the project was incredibly well-received by fisherfolk and by the TCI public in general, with broader interest expressed by the tourism industry, teachers, and politicians among others. Conducting the project was also filled with joy, especially through interactions with the most underprivileged sectors of the fishing community, in particular immigrant fishers and fish workers, who were very generous with their time, very helpful, and extremely appreciative of having resources tailored for them and written in their languages.

Written by Marta C. Calosso and John A.B. Claydon. For more information on this Darwin Plus Local project DPL00045, led by FisherFolkFirst, please click here.

English video:

Creole video:

Spanish video:

Additional photographs:

John Claydon, FisherFolkFirst, showing the fishing regulations poster to fish workers at Provo Seafood processing plant, Five Cays, Providenciales. Credit - Marta Calosso.

Back

Back